Mubarak Raji

LLB (Bayero) BL (Lagos) LLM (Illinois)

PhD student, School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA

Devyn Wilder

BS (Virginia Commonwealth University) MLIS (University of Washington Information School)

PhD student, School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA

Valentine Ugwuoke

LLB (Nigeria) BL (Lagos) LLM (Illinois)

PhD student, School of Information Sciences at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, USA

Masooda Bashir

PhD (Purdue University)

Associate Professor, School of Information Sciences; Associate Professor, Coordinated Science Laboratory and Information Trust Institute; Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Industrial and Enterprise Systems Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA

We thank Professor Madelyn Rose Sanfi lippo, Muhammad Hassan of the University of Illinois School of Information Sciences, and Professor Faye Jones of the University of Illinois College of Law for reading and providing helpful feedback on the draft. We also appreciate the anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable comments.

Edition: AJPDP Volume 2 2025

Pages: 1-40

Citation: M Raji, D Wilder, V Ugwuoke & M Bashir ‘An assessment of the enforcement mechanisms in African data protection laws’ (2025) 2 African Journal on Privacy & Data Protection 1-40

https://doi.org/10.29053/ajpdp.v2i1.0002

Download article in PDF

Abstract

Africa has the second-biggest population in the world, with about 1,1 billion projected internet users by 2029. This growth in internet users has made many Africans vulnerable to privacy threats. To protect their citizens’ personal data, about 38 out of 55 African countries have legislated data protection laws. While previous literature has provided valuable insights into African DPLs, most studies have focused on summarising the legal framework or comparing them to other legislations like the General Data Protection Regulation. Therefore, there is a significant gap in understanding African DPL enforcement mechanisms. Our study seeks to address this gap by identifying common, unique trends and practices in African DPL enforcement. To conduct this research, we used a rigorous qualitative evaluation method of thematic content analysis involving three independent researchers. The researchers examined data protection laws of 20 African countries, which are publicly available in English, regarding their enforcement mechanisms. Our analysis indicates that all 20 countries require a dedicated data protection authority to enforce DPLs, and the laws apply to private and public sectors. To deter privacy violations, we observed that 85 per cent of the countries prescribe administrative sanctions; all the countries have provisions for financial and criminal sanctions; we also observed that 65 per cent of the countries studied allow data subjects to seek private right of action. Furthermore, all 20 countries in our sample require data controllers to register or notify data protection authorities before data processing; 55 per cent of the countries have extraterritorial reach provisions. We believe our research is a critical step towards evaluating African DPLs, which will guide policy makers, international organisations, compliance analysts, lawyers, legislators and technology companies involved in data collection and processing in African nations. By comparing the enforcement approaches among different African countries, our findings can shape future regional policy and data protection practices.

Key words: Africa; data protection; data protection authority; enforcement mechanism; sanctions

1 Introduction

Data is the foundation of the modern world that drives innovation and fuels the digital transformation, which underscores the importance of personal data in the twenty-first century. This emphasises the growing importance of personal data in the technological era, where it has become one of the most valuable resources. Data is crucial, and it is the foundation of modern technological advancements. This accurately reflects the reality that data has emerged as the driving force of innovation in our world, as information is power and integral to economic development and wealth creation.1 Nowadays, personal data is easily accumulated using the internet, and Africa is not left out of this global trend. Africa has the second-largest population in the world, with the number of internet users increasing rapidly to about 728 million estimated users in 2024 compared to previous years and potential room for growth projected to about 1,1 billion users in 2029.2 African internet users account for the world’s highest mobile data usage, with approximately 74 per cent of users accessing the internet through mobile devices for different activities such as social media, with Facebook as the most used platform, e-commerce, online banking and mobile payment.3 The growth in internet penetration in Africa also encompasses the creation, use and sharing of ever more personal data.

With the rise in personal data generated across Africa, there is growing concern about how personal data is protected in the era of surveillance capitalism and digital colonialism. Surveillance capitalism has been defined as the ‘new economic order that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales’.4 It is the process by which technology companies accumulate vast amounts of data, often without obtaining informed consent of the data subject, in order to exert dominance, influence user behaviour, and target advertisements to make a profit.5 Surveillance capitalism underscored how personal data are integral to innovation and a tool to control the market economy, which can lead to users’ behavioural control and surveillance, making users of technology tools sacrifice their privacy in exchange for technology usage.

Surveillance capitalism involves many stages, starting from data collection to extraction. Personal data such as location data, frequently used applications and websites, online search queries, and other personal preferences or habits from technological devices, including mobile phones and smart devices (for example, smart home technologies and smartwatches) and social media platforms. The next stage is data analysis of these personal data using computer algorithms to determine individual preferences, profiling and envisage future behaviours. The personal data collected is treated as commodities, often commercialised and sold to advertising companies. Using predictive analytics, targeted and personalised ads, the advertisers recommend products to the consumer to influence and manipulate their decisions to make profits for technology companies. In the process, users’ privacy is being eroded mostly due to the absence of consent and transparency.6 One major example of surveillance capitalism is the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica controversy, where Facebook users’ the personal data were harvested without their consent. The personal data was profiled with personalised political ads targeted to manipulate and influence the political voting choice. The case later led to one of the most significant privacy violations globally, with many legal battles across different jurisdictions.7

On the other hand, digital colonialism is where enormous amounts of personal data are harvested for profit by big tech companies that exploit the lack of technology infrastructure, access to the internet, competition, and data protection laws. Coleman explained that digital colonialism is mainly targeted at underdeveloped and developing countries, mostly in the Global South, by powerful technology companies in the Global North. Some characteristics and factors that enable digital colonialism include the digital divide, data extraction and exploitation, and reliance on the Global North for digital infrastructure such as social media, cloud storage, internet services and undersea cables. Others include unequal economic powers and technological monopoly since much of the internet technologies are developed and controlled by the Global North.8

Digital colonialism has been described as another form of modern-day colonialism. Classic colonialism occurred with the exploitation of raw materials during the scramble for Africa and colonisation using imperial trading corporations such as ‘the British South African Company, the Germany East African Company, the Imperial British East African Company, and the Royal Niger Company as conduit pipe’ leading to a history of mistrust. For example, Facebook Free Basics and Google C-squared programmes have been described as examples of digital colonialism in Africa.9

While surveillance capitalism occurs globally, digital colonialism is mainly targeted at less-developed societies. However, both pose a risk to human privacy, aimed to acquire personal data and for profit. These may lead to the erosion of privacy in many ways as personal data is collected from digital devices, smart technologies, IoT systems and search engines, and social media to capture behavioural data, manipulate users’ habits and choices and enhance technology surveillance through predictive algorithms.10 Additionally, like other regions of the world, privacy threats expose Africans to vulnerability, such as cybercrimes, such as stolen identity and internet fraud and cyberattacks.

Furthermore, there has been an increase in reported data breaches by data controllers and processors and data protection authorities imposing sanctions on private organisations and government actors in Africa. The most recent incident is the investigation and imposition of Nigeria’s US $220 million fine on Meta, arguably the most significant fine in Africa compared to other penalties, which average less than US $1 million.11 Other prominent data protection violations in the last three years that have attracted imposition of sanctions include Sokoloan’s case in Nigeria in 2021;12 the Kenyan Office of Data Protection Commissioner’s acceptable on Chinese Oppo mobile in 2022;13 fines imposed on Africell mobile telecommunication company in Angola in 2023;14 the Yango application case in Côte d’Ivoire in 2023;15 Sincephetelo Motor Vehicle Accident Fund’s fines on Eswatini in 2023;16 and sanctions on the South African Department of Justice and Constitutional Development.17 More recently; it was reported that there was the unauthorised sale of personal data domiciled with the National Identity Management Commission in Nigeria, which the government initially denied but has commenced investigations.18 Also, there is a growing menace of data protection violations and harassment by online lending application companies with scenarios in Nigeria, Kenya and Ghana.19 The above concerns make assessing the enforcement of data protection laws on the African continent crucial.

Also, technological advancement has significantly increased, and one approach to data protection around the globe is the enactment of data protection laws to protect data privacy, extending beyond the traditional scope of privacy. As Warren and Brandeis rightly predicted, mechanical devices could pose potential threats and enhance privacy invasion without adequate legal measures.20 The prediction has led many countries, political and economic unions, corporate associations and international organisations to develop rules, regulations, conventions, treaties or laws to regulate data protection. Africa has emerged as one of the leading regions with various data protection laws enacted by countries, and while the world is not paying sufficient attention, the number of African countries with data protection legislations has dramatically increased.21 Some African countries require their citizens’ personal data to be protected even if the data is processed in a foreign country, which is similar to the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which mandates the safeguarding of EU citizens and residents’ personal data outside the EU. This is another point of concern for data processors and controllers possessing the personal data of Africans around the globe to be cognisant of their respective approach to data protection regulation. Hence, compliance with these data protection laws needs to be examined.

As of 31 March 2024, 38 out of 55 African countries have taken drastic measures to protect personal data by enacting country-specific data protection legislations in addition to other international instruments concurrently in force across different African sub-regions. These international instruments are discussed in detail in part 2.3 below. It is remarkable and laudable that African countries have taken giant steps with the enactment of data protection laws. While legislating data protection laws (DPLs) is the essential step towards privacy protection, it is equally important to determine the enforcement mechanisms that ensure data controllers’ and processors’ adhere to the legalisations; otherwise, the purpose of enacting those laws will be futile. Much of the previous literature has examined the African international and regional approach to data protection regulation,22 tracing the historical origin of data in Africa,23 data protection authorities,24 and the legal framework of regulating data protection in several African countries. However, this study intends to address the research gap in assessing the African enforcement patterns of national data protection laws, which is a critical gap in literature.

In this study, we examined the enforcement mechanisms of data protection laws in 20 African countries to assess how personal data are safeguarded and the possible repercussions of violating data protection legislative frameworks.25 In addressing the method of enforcing the data protection laws, we asked the following research questions: What enforcement approaches do African countries use to ensure adherence to data protection laws? Who is saddled with the responsibility of enforcing these laws? What kind of sanctions are specified in the laws?

2 Background

2.1 Privacy and data protection

Privacy is a complex concept that lacks a universally-accepted definition, like several concepts in the social sciences.26 Broadly speaking, privacy pertains to an individuals’ capacity to manage who can access their personal data, including their body, family, home, communication or personal information.27 Warren and Brandeis foresee the future when they argue that mechanical devices may cause potential threats and enhance privacy invasion if adequate legal measures capture the present-day reality of data privacy in the internet era.28 Their work accounted for how the right to privacy was birthed from the rights to life, property, and ‘to be let alone’29 and how it was accepted under common law initially as a tortious liability.30 The right to privacy was later codified as a fundamental human right to privacy under several international treaties, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948 (Universal Declaration),31 and national constitutions in Africa.32

Privacy can be classified into different types: ‘bodily privacy’; ‘spatial privacy or territorial privacy’; ‘behavioural privacy’; ‘proprietary privacy’; ‘associational privacy’; ‘intellectual privacy’; ‘decisional privacy’; ‘communicational privacy’; and ‘informational privacy’.33 Informational privacy is the focus of this study, which deals with collecting, processing, retaining and using personal data that can be used to identify an individual and how these personal data can be protected.34 It is worth mentioning that the Universal Declaration broadly defined human rights to privacy and provided that ‘no one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.’35 However, data protection focuses on a narrower perspective regarding privacy protection, which involves holistic and sociotechnical aspects of privacy protection, especially information privacy.36

Informational privacy is otherwise known as ‘data privacy’ or ‘privacy’ in North America, whereas it is referred to as ‘data protection’ in most European legislations and literature.37 In most African literature and legislation, the data privacy is described as data protection. Hence, the data protection nomenclature will be adopted in this work.

2.2 Notion of privacy in Africa

There has been an ongoing debate about whether the notion of privacy is indigenous to Africa. For example, one champion of this debate is Makulilo.38 He argues that the Western conception of privacy and individualism was imported to Africa, which influenced the development of privacy on the continent.39 He buttresses his arguments with the fact that privacy rights were clearly omitted in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter), which indicated that privacy was not a popular concept.40 He also argued that Africa has collectivist values relying on the concept of ubuntu, which originated from Southern Africa.41 Ubuntu has been defined to mean that a person ‘is part of a larger and more significant relational, communal, societal, environmental and spiritual world’.42 Ubuntu encourages openness, community relationships, solidarity and transparency, while privacy can be termed ‘secrecy’, which is not in tandem with communalism values.43 Several African societies have the equivalent of ubuntu and its communalism values, especially within families.44 One way of conceptualising privacy in the Western world is that privacy is seen from an individual, personal space, autonomous, and personhood perspective, which is contrary to the concept of ubuntu, which underscores communal mindset, collective well-being, and communal accountability. The concept of ubuntu also raises the issues of collective privacy over personal privacy, where the conduct of a person can reveal the unique behaviour and identities of people in the families or communities.45 For example, one of the ways to illustrate the communal approach to privacy is through the lens of genetic privacy. Imagine a family member shares their DNA for ancestral genetics; the individual’s conduct can reveal the genetics of the entire family and make their genetics data available on the genetics database, which can be used to trace the ancestral origin, paternity and criminal investigation. It is essential to observe that the concept of ubuntu and the Western notion of privacy raise cultural perspectives and cross-continental approaches to privacy conceptualisation, which warrants further research through future studies.

On the contrary, Yilma and Jimoh have countered Makulilo’s argument that the theory of privacy was foreign to Africa.46 They both argued that African societies are familiar with privacy, which is deeply rooted in their culture. Jimoh made some exciting illustrations to prove that privacy exists in several heterogeneous African societies and explained that in many family compounds, extended family members have their houses close to one another and have a common area. However, the homes are constructed in a way that respects the privacy of each nuclear or polygamous family in Yorubaland, predominantly in the southwest region of Nigeria and some parts of the Benin Republic.47 He further buttresses his argument by using Àroko in the same Yoruba society, which is used in secret communication, indicating that privacy existed in pre-colonial Africa. Àroko utilised pre-packaged materials with symbolic elements to convey messages to those who understood the symbols.48 He also cited the privacy values of the Amhara societies in present-day Ethiopia, where it is prohibited to enter another person’s house without proper acknowledgement or being escorted inside, among other examples.49 Yilma and Jimoh also contended that the mere fact the human right to privacy was omitted in the African Charter does not mean that privacy is alien to Africa, as posited by Makulilo, and can be described as an omission during the drafting stage.50 Additionally, the fundamental right to privacy is already acknowledged in the constitutions of several African nations well ahead of the promulgation of the African Charter in 1981.51

Furthermore, most African countries were colonised by European countries. This shaped the legal systems of many African countries after gaining independence, mainly civil law or common law systems, legislative enactments, and the administration of justice.52 After colonisation, the legislative frameworks in Europe still affect Africa. One clear example is the adequate level requirements under articles 25 and 26 of the EU Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC, which prohibited the transfer of Europeans’ personal data to non-EU or foreign countries that did not fulfil the adequacy test, has an impact on data protection laws in Africa.53 Also, some African countries are signatories and have ratified the Convention for the Protection of Individuals about Automatic Processing of Personal Data of the Council of Europe.54 Additionally, Cape Verdean data protection law, which was the first national data protection law in Africa, was fashioned out of its colonial master, Portuguese data protection law, and France provided support to the Francophone African countries in developing their data protection laws.55 Lately, many African countries have adopted the EU General Data Protection Regulation 2018 (GDPR) approach to data protection legislation. This can justify Bradford’s postulation that Europe influences regulations in the world on data protection, anti-trust, and environmental sustainability, among others, which has been termed the ‘Brussels effect’.56 The above demonstrates that although external influences may hasten the development of data protection laws in Africa, privacy is not entirely new to some African societies.

2.3 African Union and regional data protection instruments

In the quest to safeguard and regulate personal data, there are three major approaches to data protection regulation in Africa, which can be categorised into the African Union (AU) approach, regional economic communities approach and national approach. In this part, we discuss several initiatives for data protection that are in place in Africa.

The African Union or continental approach is championed by the AU, a union of all 55 African countries.57 The AU emerged from the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) that was initially created in 1963 to foster harmony and ensure collaboration among African countries.58 In 2014 the AU adopted the AU Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (Malabo Convention) on 27 June 2014 at Malabo, Equatorial Guinea.59 The Malabo Convention contains provisions governing ‘electronic transactions,’60 ‘personal data protection,’61 and ‘cybersecurity and cybercrime.’62 Nineteen countries have already endorsed the Malabo Convention by signing it, and it entered into operation on 8 June 2023, approximately nine years following its adoption, when the fifteenth country ratified and deposited the Convention.63 However, enforcing the Malabo Convention is a work in progress due to late ratification by at least 15 countries,64 which made it in force nine years after its adoption and non-ratification by other countries, funding problems and absence of political will to ensure implementation.65 Also, Africa does not have a continental or regional enforcement authority such as the European Data Protection Broad which may affect its effective implementation, mainly due to the nature of the Malabo Convention, which must be ratified first before becoming binding on any country, unlike the EU GDPR, which is binding and applicable in any EU country since it comes into force. Recently, the AU approved the AU Data Policy Framework in 2022.66

More recently, members of the Organisation of the African, Caribbean and Pacific States signed a Partnership Agreement with the EU and its member countries (Samoa Agreement) to advance human rights, the rule of law and democracy, enhance peace and security, and foster economic change, among others, on 15 November 2023.67 Article 15 of the Samoa Agreement mandates parties to have adequate data protection legislation, monitoring enforcement, and establishing independent supervisory authorities.68

2.3.1 Regional economic communities’ approaches

Africa is divided into five regional divisions: Central Africa, East Africa, North Africa, Southern Africa and West Africa. Some of these sub-regions formed regional economic communities to promote trade and economic harmony. These regional economic communities have prescribed rules to guide data protection, and in this part we discuss some of the data protection initiatives.

Several African regional economic communities prescribed treaties or non-binding model laws for adoption by the participating countries. Prominent among them is the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which was established in 1975 and comprises 15 West African countries intending to foster ‘economic integration’ among participating states.69 In 2010 the member states adopted the Supplementary Act A/SA.1/01/10 on Personal Data Protection within ECOWAS to govern data protection.70 The law was the first regional data protection instrument to be in operation in Africa.71

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is a Southern Africa-based regional economic community with 16 member states.72 It was initially established as the Southern African Development Coordination Conference in 1980 to promote economic integration among member states.73 The SADC prescribed the SADC Model Law on Data Protection in 2013,74 produced as part of the International Telecommunication Union’s Harmonisation of the ICT Policies in Sub-Saharan Africa project.75 It is a model law for participating states to adopt and it is non-binding.76

The East African Community (EAC) is another regional bloc for political and economic cooperation with eight member states.77 The EAC presented a draft of the EAC Legal Framework for Cyberlaws in 2008.78 The frameworks contain provisions on electronic transactions, compute crime, consumer protection and data protection. The SADC Model Law is a guide for member states and is not a binding authority.79 With all these regional efforts, having a continental approach to enforcing data protection laws is still a work in progress due to non-ratification of the Malabo Convention 2014 and the need for a regional enforcement authority.80

2.4 National data protection laws

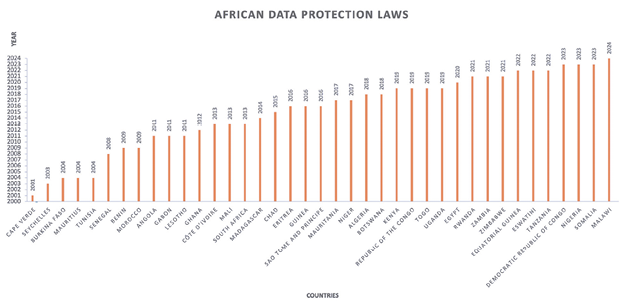

As stated earlier, some countries worldwide protect fundamental right to privacy in their national constitutions. About half of the 55 African countries enumerated privacy rights as one of the fundamental human rights protected in their constitutions.81 The right to privacy broadly guarantees privacy in ‘homes, correspondence, telephone conversations, and telegraphic communications,’ but excludes clear provisions on data protection principles.82 However, numerous African countries have passed data protection laws to ensure data controllers and processors lawfully acquire, control, store and process their citizens’ personal data. For example, Cape Verde became the first African nation to enact data protection laws in 2001, and several other countries followed suit. As of the end of March 2024, 38 African countries have enacted data protection legislations, while 17 countries have not passed data protection laws. See Figure 1 for African countries with and without data protection laws and Figure 2 for the year of enactment of each data protection law in Africa. However, Cameroon, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Namibia have drafted data protection bills pending passage into law.83

Figure 1: Countries with and without Data Protection Legislation in Africa

Figure 2: Year of enactment of data protection laws in Africa

Figure 3: African countries with amended data protection laws

It is also imperative to observe that about seven countries have amended their data protection legislations after its first enactment. The countries are Cape Verde,84 Seychelles,85 Burkina Faso,86 Mauritius,87 Gabon,88 Mali89 and Niger.90 For details, see Figure 3 above for the years of the amendment.

2.5 Enforcement of data protection laws

In an ideal society, all and sundry are expected to obey laws; however, legislators envisage that there will be violators. Hence, data protection laws prescribe some enforcement methods to ensure compliance and consequences of violations and non-compliance in the form of sanctions. Enforcing data protection laws involves some key players, measures and consequences of non-compliance. Under the comprehensive data protection approach, an enforcing body is saddled with the responsibility of monitoring, administering, regulating, enforcing and implementing data protection laws and overseeing personal data collection, storage, transfer, and lawful processing against the private and government sectors.91 This enforcing body is mainly called data protection authority (DPA) or independent supervisory authority. This is comparable to article 51 of the EU GDPR, which mandates that EU member countries have a supervisory authority. However, the South African Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) mandates the establishment of the Information Regulator. Data protection authorities can issue regulatory guidance or regulation under data protection laws, oversee data protection compliance, investigate personal data violations and impose sanctions. Data protection authorities can also register data controllers and processors and maintain the register of controllers and processors. However, it is essential to observe that this registration is only mandatory if the country requires it.92 In this study, we assess whether 20 African data protection laws have provisions for establishing independent data protection authorities or designating an existing government agency as DPA. We also looked at whether the DPA can register data controllers and processors. Some African countries, notably Nigeria and South Africa, have already established independent DPAs. In contrast, countries such as Eswatini, Zimbabwe and Rwanda have designated existing government entities and agencies as supervisory authorities.93

Sanction is the ‘provision that gives force to a legal imperative by either rewarding obedience or punishing disobedience’.94 In other words, sanctions are an enforcement mechanism with the force of law. It penalises non-compliance to deter an unlawful act and encourages obedience to law and order. Sanctions can be administrative, civil, financial or criminal sanctions.95

A sanction is administrative when ordered and imposed by a data protection authority, an administrative body, and not by a court of law, which can be informed of administrative penalties.96 The court imposes civil sanctions as compensation or remedy to the plaintiff (data subject) for the injury caused by the defendant (violators of data protection laws), which is a form of a civil remedy or privacy right of action.97 A data subject for which a data controller or processor has violated their data protection rights can institute a civil action against the violator before a court and will be entitled to damages as compensation without prejudice to other administrative remedies available with the supervisory authority is a classic example of civil sanction.98

Financial sanctions involve paying money as a penalty, mainly in the form of fines for violating data protection laws.99 Under EU GDPR, the supervisory authority has the power to investigate data breaches and impose administrative fines of ‘20 000 000 EUR, or in the case of an undertaking, up to 4 per cent of the total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher’ can be classified as a financial sanction.100 It is imperative to mention that a financial sanction can be an administrative sanction if it is imposed by a data protection authority and a criminal sanction if the court imposes it. A criminal sanction data violator is charged, prosecuted, evidence tendered, convicted, and sentenced to prison or a fine imposed.101 The enforcement approaches of data protection laws in 20 African countries will be evaluated based on administrative, civil, financial or criminal sanctions.

These laws specify who is responsible for enforcement and prescribe some enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance and sanctions for violators. The African countries’ enforcement approach will be assessed based on whether they are administrative or civil sanctions, which are acceptable in the EU, or criminal sanctions, which are another form of sanction. The research questions and hypotheses for this topic are provided in this article under the introduction.

3 Related work

In the last two decades, several authors have written on legal frameworks for African data protection. Similarly, several African countries have enacted new data protection laws in the evolving legal space. Notably, existing literature in Africa focuses on the historical account of data protection,102 international and regional instruments on data protection,103 data protection authorities,104 cross-border transfer of data,105 and the legal framework of regulating data protection in several African countries, with Makulilo championing the discourse.106 While we could not find prior studies examining several enforcement mechanisms of African data protection laws, we will review relevant articles related to this topic.

More specifically, Babalola and Sesan examined the role of data protection authorities as independent supervisory authorities in 30 African countries in enforcing data protection laws from 2007, when Burkina Faso first established a data protection authority in Africa, to 2021.107 They analysed countries that have created data protection authorities, the mode of appointing officials to determine their independence and interference from their government, investigations carried out, decisions taken and transparency in enforcing data protection laws. This report is relevant to our study as it underscores the importance of data protection authority in enforcing data protection laws.

In another study by Bryant, he discussed the drawbacks, prospects and state of data protection in Africa in the technology era.108 He submitted that colonialism and external influence aided the development of data protection laws in Africa.109 He briefly discussed the legal framework of data protection in Ghana, Nigeria, Tunisia, South Africa, Mauritius and Angola.110 He identified non-enforcement and misuse of personal data in the public sector and enforcing data protection on multinational companies as a significant challenge.111 He also argued that external actors, mainly the West and China, may expose Africa to more vulnerability.112 He concluded by recommending, among other things, the need for effective enforcement to ensure compliance with data protection laws.113 His work is one of the motivations for this study, and it is relevant to examine whether the government actors are bound by data protection laws and enforcement patterns in 20 African countries.

In a more recent article, Abdulrauf discussed African data protection legislation approaches.114 He argued that external influence, especially the EU and internal influence, especially African regional instruments, affects the approach to data protection regulation, and some countries have created supervisory authorities to enforce data protection laws and identified that some countries mandate government department to administer data protection law instead of creating an independent data protection authorities.115 He enumerated some approaches, such as protecting vulnerable groups, alternative dispute resolution, and legislation in the local African language.116 He made a case for the Africanisation of data protection laws.117 His work is related as it focuses on more general approaches to data protection. Hence, this article pays more attention to enforcement approaches.

Voss and Bouthinon-Dumas explained the concept of sanctions under the EU GDPR.118 They stated that supervisory authorities can enforce the GDPR and could impose sanctions. They further argued that the GDPR has extraterritorial applicability, which affects the United States tech companies; hence, there is a need for these companies to comply with the GDPR to avoid huge sanctions just like sanctions previously imposed under EU competition law.119 They explained the kinds of sanctions, including administrative sanctions imposed by data protection authorities as government agencies, financial sanctions in the form of money for GDPR violations, regulatory sanctions that can be enforced on companies that are regulated by regulatory authorities, civil sanctions gives data subject private right to action to approach the court for remedies, criminal sanction is imposed after criminal prosecution and conviction.120 They argued that sanctions could be for rehabilitation, retribution, reparation, confiscatory, expressive or normative functions, deterrence or incapacitation.121 They also considered the sanctions under the EU data protection directive and GDPR.122 It is important to note that their work examining enforcement approaches was a motivating factor for this study.

4 Methodology

This study was a qualitative study examining the various approaches to enforcing data protection laws enacted in 20 African countries from 2000 to 2024, which were publicly available online and available in the English language to be able to conduct thematic content analysis, followed by the development of a structured coding strategy. After conducting preliminary analyses, three co-authors independently reviewed and analysed the 20 selected data protection laws based on a codebook developed for this study as independent researchers.

In our research on identifying data protection laws in Africa, we identified 38 African countries out of 55 that have enacted data protection laws as of March 2024. Upon downloading all the laws, we observed that some laws were in English and other languages (Arabic, Portuguese, French and other African languages). Hence, it was determined that we would only examine the laws that had an English language version publicly available as an inclusion criterion for the law to be analysed in this study. Thus, we focused our analysis on the 20 African countries with an English version of their law that can be downloaded online. We excluded any laws that did not have an English version as of March 2024 to effectively determine their enforcement patterns. The English criterion was introduced because the research was conducted at a Midwestern university in the United States, and all the researchers were fluent in English. This criterion enabled them to examine and analyse the laws critically and directly from the published version without translation bias or oversight. It also enabled the researchers to conduct consistent comparisons of these laws to observe and identify common, unique trends and practices in enforcing data protection laws in Africa using a common language among them. Therefore, we acknowledge that our findings represent only the 20 countries included in this study and hence it may not generalise to all the 55 African countries. Nonetheless, we did ensure that all the five sub-regions in Africa, Central Africa, East Africa, North Africa, Southern Africa and West Africa, are represented in this study to be inclusive of the various regions.

The 20 countries selected for this study include Benin, Botswana, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Eswatini, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Nigeria, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Somalia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The following parts describe the scientific and systematic approach we used to conduct this research.

Step 1– Gathering African data protection laws

To identify and determine which African countries have data protection laws, we commence the research by reviewing existing literature and reports on African data protection laws.123 We also conducted an extensive internet search to identify websites and repositories that will include African data protection laws, such as the United Nations (UN) Trade and Development (UNCTAD),124 Morrison Foerster,125 DLA Piper,126 Data Protection Africa,127 OneTrust Data Guidance,128 and International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP)129 websites. In collating the data protection laws, we utilised the IAPP Resource Centre and OneTrust Data Guidance (regulatory research software) as of March 2024 to ensure we had the same set of laws. The two databases led us to the same countries’ official websites, where the laws were downloaded. However, there was an exception in the case of Egypt, where there was no link to the country’s government website; the law was downloaded from the IAPP Resource Centre.

We took measures to ensure that we selected the official and most recent versions of the laws by comparing the different files available on the repositories and resources we accessed, ensuring that the version we analysed was the official version released by the government of the selected countries. It is important to note that data protection laws are an evolving landscape in Africa. Therefore, in this study, the version of the reviewed and analysed laws was publicly available as of March 2024. See Figure 1 above for the list of African countries with or without data protection laws.

Step 2 – Examining the enforcement section and development of the codebook

Upon selecting the 20 countries to be further evaluated in the study, we initially read through the laws for the common themes and trends in enforcing data protection laws, which served as the basis for developing our codebook. The codebook was created to ensure objective and effective analysis, comparison of specific criteria examined, and consistent evaluation of each selected data protection law. The table below provides the specific criterion examined. For a description of what each criterion entails, see step 3 below.

|

Country |

Legislation |

Enactment Date |

Data protection authority |

Admini- |

Financial Sanction |

Criminal Sanction |

Civil Action Register of Data Control- |

|

Register of Data Controller |

Extraterri- |

Compliance Audit |

Applicabi- |

We created a codebook listing each of the 20 countries. For each country, three independent researchers reviewed and analysed the enforcement sections for the following criteria and coded them as either ‘Yes’ or ‘Not mentioned’. For those criteria coded as ‘Yes’, we also noted the specific language, variation in description, similarities, and differences for each country and across the countries included in our study.

Each researcher made their coding independently for each of the selected countries before sharing their analysis with other researchers. If there was a disagreement in coding any criteria, a group meeting was scheduled with the PI to discuss the discrepancies and reach a consensus if needed.

After the three independent researchers concluded reviewing the laws and coding, they met and agreed to label their findings in a separate codebook for inter-rater reliability. In labelling, two code definitions were used; the word ‘Yes’ stands for when the laws expressly or implied mentioned an act and ‘Not mentioned’ stands for issues not covered in the statutes or unclear.

In order to assess the agreement between the three raters, we decided to use Fleiss’ Kappa for overall distributions, a statistical method for calculating reliability. Upon finishing the assignment of labels in the first iteration, each rater returned spreadsheets where all data was moved into a singular spreadsheet. Using RStudio and library package ‘irr’ containing the Fleiss’ Kappa function, the calculation initially resulted in 0,35 or 35 per cent agreement among the three raters. Interpreting the results, an agreement of 35 per cent meant ‘fair agreement’ between the three raters. Due to a lower percentage of agreement, we decided on a second iteration consisting of a review or a process called rater monitoring and calculating results again.

For the second iteration, the raters unanimously agreed to reconnect to discuss the results of the labels. During this discussion, each rater was responsible for justifying their label and providing proof. If a rater had a label of ‘Yes’, there was documentation from said rater citing where the justification of the label would be located. A good illustration is a case of examining administrative and financial sanctions for Benin and Côte d’Ivoire, which were not easily comprehensible because the laws were originally drafted in French. Still, the data protection authorities have English versions on their website, which were relied upon. This usually included a section or article number used to identify the area. If a rater had a label of ‘Not mentioned’, there was no documentation provided signifying its absence.

Additionally, we validated our application of a consistent definition for each category, and the primary discussion was about implied statements versus explicit statements. Upon further analysis, the research team decided to mark a criterion as ‘Yes’ only if there was explicit content supporting those criteria. Therefore, the three researchers conducted a second round of review and analysis of the laws to recode, and this second round yielded a higher level (77 per cent) of agreement among the raters. This higher level of agreement was achieved because instead each was asked to provide content justification or lack thereof for their codlings. In addition, there was a discussion among the raters about each criterion, and the ratter had the option of keeping or changing their label. A good example of this is examining administrative sanctions for Zimbabwe, where the raters are not unanimous even after a meeting. The Zimbabwe Data Protection Act law stipulates that the Zimbabwe Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority POTRAZ must approach the court for any administrative act not in compliance with data protection principles. Two of the raters do not consider this an administrative sanction.

It is important to note that there was no obligation for unanimous agreement or a rater to change their label. While we had a high agreement, we still wanted to investigate the 23 percent disagreement to better understand what may have led to those discrepancies. In the process of this discussion between the raters, after providing justification, each rater had the option of keeping or changing their label. There was no obligation for unanimous agreement or for a rater to change their label.

After completing the second iteration of labels, we ran Fleiss’ Kappa in RStudio again, and the calculation resulted in 0,77 or 77 percent agreement among the three raters. This result indicated excellent agreement between the three raters. A 100 percent agreement could not be reached due to a lack of consensus during the discussions. One major contributing factor was the researchers examining a translated version of the laws and, therefore, facing the challenge of language and translation variations where the content was unclear, making it difficult to make a solid determination. We decided as a group to leave labels where they were if criteria could not be identified clearly.

Step 3 – Analysing the specific content of the enforcement section

We continued employing a rigorous qualitative evaluation method involving three independent researchers in this step, which focused on analysing the content of a given criterion once it was coded as the law addressing those criteria.

To determine whether a selected country has a data protection authority specified in their laws, we checked if the law mandates the creation of data protection authorities or designates an existing government agency as a regulator of the country’s data protection sector. For example, section 1(1) of the Ghana Data Protection Act establishing a data protection authority for Ghana provides that ‘there is established by this Act a Data Protection Commission’.

To determine if a sanction is administrative, we studied the laws to observe whether the data protection authority can prescribe any of these administrative sanctions: cessation; the temporary or final withdrawal of authorisation to process data; warning; notice to stop; order to carry out specified steps; refrain from an act; and administrative fines. For example, section 42(2) of the Malawian Data Protection Act stipulates:

(2) The compliance order issued by the authority under subsection (1) may include any of the following –

- an order requiring the data controller or data processor to comply with a specified provision of this act;

- a cease and desist order requiring the data controller or data processor to stop or refrain from doing an act which is in contravention of this act;

- an order requiring the data controller or data processor to pay compensation to a data subject affected by the action or inaction of the data controller or data processor;

- an order requiring the data controller or data processor to account for the profits made out of the contravention;

- an order requiring the data controller or data processor to pay an administrative penalty not exceeding k20,000,000; or

- any other order as the authority may consider just and appropriate.

Concerning financial sanctions, we looked for words such as a particular amount of money, financial sum, or percentage of the data controller’s annual return of the preceding financial year. The financial sanction can be in the form of administrative or criminal fines.

Section 63 of the Kenyan Data Protection Act is apt on this, which provides:

In relation to an infringement of a provision of this Act, the maximum amount of the penalty that may be imposed by the Data Commissioner in a penalty notice is up to five million shillings, or in the case of an undertaking, up to one per centum of its annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is lower.

For civil sanctions, which allows the data subject, the victim of a data violation, to institute an action before a court against the data controller or processor to seek damages for the injury suffered, we checked the laws for words such as compensation, private right of action, civil remedies, and damages and their equivalents. A good instance of this is section 51 of the Nigerian Data Protection Act, which provides that ‘[a] data subject, who suffers injury, loss, or harm as a result of a violation of this Act by a data controller or data processor, may recover damages from such data controller or data processor in civil proceedings’.

As for criminal sanctions, we studied the laws to see if the laws prescribed offences and punishments, such as criminal fines, imprisonment terms, forfeiture, or words such as convict and crime, are contained in the law. Article 56 of the Rwandan Data Protection Act provides:

A person who accesses, collects, uses, offers, shares, transfers or discloses personal data in a way that is contrary to this Law, commits an offence. Upon conviction, he or she is liable to an imprisonment of not less than one (1) year but not more than three (3) years and a fine of not less than seven million Rwandan francs (RWF 7 000 000) but not more than ten million Rwandan francs (RWF 10 000 000) or one of these penalties.

On registration of the data controller, we checked whether the mandated data controller registered with the data protection authorities before commencing processing personal data or whether the data protection authorities are mandated to keep the data controller’s register. An illustration of this is captured under section 29 of the Ugandan Data Protection Act thus:

(1) The Authority shall keep and maintain a data protection register.

(2) The Authority shall register in the data protection register, every person, institution or public body collecting or processing personal data and the purpose for which the personal data is collected or processed.

(3) An application by a data controller or other person to register shall be made in the prescribed manner.

Also, we reviewed the laws to see whether they expressly specify applicability to public and private sectors or every controller without excluding the government. Specifically, section 3 of the Mauritius Data Protection Act provides:

(1) This Act shall bind the state.

(2) For the purposes of this Act, each Ministry or Government department shall be treated as separate from any other Ministry or Government department.

(3) This Act shall apply to the processing of personal data, wholly or partly, by automated means and to any processing otherwise than by automated means where the personal data form part of a filing system or are intended to form part of a filing system.

(4) This Act shall not apply to –

- the exchange of information between Ministries, Government departments and public sector agencies where such exchange is required on a need-to-know basis;

- the processing of personal data by an individual in the course of a purely personal or household activity.

(5) Subject to section 44, this Act shall apply to a controller or processor who –

- is established in Mauritius and processes personal data in the context of that establishment; and

- is not established in Mauritius but uses equipment in Mauritius for processing personal data, other than for the purpose of transit through Mauritius.

(6) Every controller or processor referred to in subsection (5)(b) shall nominate a representative established in Mauritius.

(7) For the purpose of subsection (5)(a), any person who –

- is ordinarily resident in Mauritius; or

- carries out data processing operations through an office, branch or agency in Mauritius, shall be treated as being established in Mauritius.

Lastly, to determine whether the laws have extraterritorial effects, we review the laws to see if they specify that the laws apply to data controllers or processors who are not domiciled in a country but process personal data of the country’s residents. Section 2(1)(c) of the Nigerian Data Protection Act provides that ‘the data controller or the data processor is not domiciled in, resident in, or operating in Nigeria, but is processing personal data of a data subject in Nigeria’.

5 Results

Data protection is an evolving landscape in Africa. As of March 2024, we could trace 38 out of 55 African countries having all-inclusive data protection laws and 17 countries without data protection laws.130 Cape Verde was the first African nation to pass a data protection legislation, and Malawi was the latest country with the signing of the Malawian Data Protection Act in January 2024.131 The list keeps increasing as some other countries have released data protection bills, which are waiting to be enacted into laws before their legislative houses.132 Other results of our study will be presented in this part, and further explanations will be provided under discussions.

Among the 20 countries selected for this study, 15 had dedicated parts for enforcement with different legal terminologies, which are enumerated in the table below. However, we do not see dedicated parts for enforcement in five countries, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritius, Seychelles, Zambia and Zimbabwe, but several sections of the laws contain enforcement provisions.

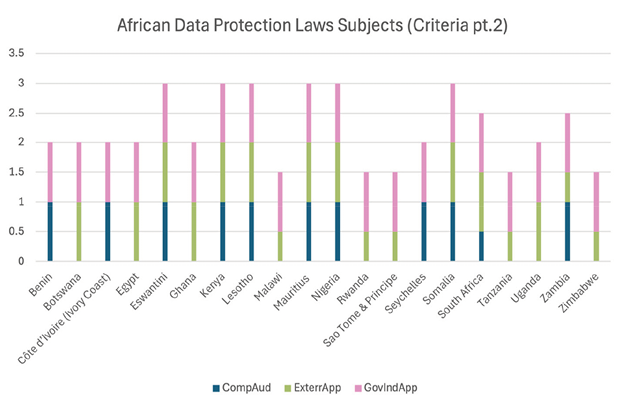

Figure 4: Administrative, financial and criminal sanctions by country

Figure 4 is a bar chart showing the classification of sanctions as administrative, financial and criminal sanctions by the 20 African countries we examined in this study. Regarding administrative sanctions, we observed that 17 of the 20 selected African countries empower the data protection authority to levy administrative sanctions for violating their data protection laws. However, there was some uncertainty for us in making a final determination on administrative sanctions for the three countries, Lesotho, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

For financial sanctions, our analysis indicated that all 20 selected African countries authorise data protection authorities (in the form of administrative sanctions) or the court (in the form of criminal sanctions) to impose financial sanctions on data controllers or processors who violate data protection laws.

Violations of data protection laws may attract criminal punishments. Our examination revealed that all the 20 countries selected in this study have provisions for criminal sanctions in their data protection laws.

Figure 5: Data protection authorities, civil action, and data controllers’ registration by country

Figure 5 is also a bar chart indicating countries that provide for the formation of data protection authorities to enforce data protection legislations, countries that allow data subjects to commence civil actions to seek compensation for damages resulting from data violations through civil remedies, and countries that mandate the registration of data controllers and processors or notification data protection authority before data processing the 20 African countries selected for this study.

Concerning the data protection authority, the three independent researchers agreed that all the 20 selected African countries in this study have provisions for establishing a data protection authority as the government agency saddled with responsibility for the administration, execution, and implementation of data protection laws in each country.

Concerning civil sanctions, our assessment revealed that a data subject has a private right of action in 13 out of 20 selected countries. The countries are Benin, Botswana, Egypt, Eswatini, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Nigeria, São Tomé and Príncipe, Seychelles, Somalia and South Africa. However, we cannot find civil sanctions in data protection laws in four countries: Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritius, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. However, there was uncertainty for us in making the final determination for three countries’ data protection laws containing civil sanctions or private rights of action: Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia.

On registration of data controllers and processors, our review indicates that the selected 20 African countries mandate data controllers and processes to register or notify the data protection authority before controlling or immediately after collecting personal data.

Figure 6: Compliance audit, extraterritorial applicability, and applicability by country

Figure 6 is another bar chart highlighting countries that make provision for regulatory compliance audits, countries whose laws have extraterritorial reach (meaning the laws are applicable beyond the countries’ borders) and the applicability of data protection laws to the public and private sectors in the selected 20 African countries in this study. For a more detailed explanation, see the discussion in part 6 below.

Regarding compliance audit, we observed that nine out of the 20 countries, or 45 per cent of countries being assessed, did not have an explicit compliance audit process mentioned or outlined in their data protection laws, namely, Botswana, Egypt, Ghana, Malawi, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. We observed that ten countries made provisions for compliance audits, including Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Estwani, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, Nigeria, Seychelles, Somalia and Zambia. However, there was uncertainty, and we could not make a final determination for South Africa.

We observed that data protection laws have extraterritorial effect provisions, meaning that data controllers or processors who are not domiciled in a country but process personal data of the country’s residents may be mandated to obey the country data protection law, just like the EU GDPR. Our review showcases that the data protection laws of 11 out of the 20 selected countries have extraterritorial effects. The countries are Botswana, Egypt, Eswatini, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, Nigeria, Somalia, South Africa and Uganda. Similarly, we could not find provisions on extraterritorial applicability in the data protection laws of 3 countries, namely, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire and Seychelles. However, there was uncertainty, which prevented us from making final determinations concerning six other countries, namely, Malawi, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

On the applicability of data protection laws to the public and private sectors, we observe in our study that the selected 20 data protection laws apply to both government and industry. In other words, data controllers and processors in the public and private sectors are obligated to adhere to data protection laws; otherwise, they will be liable if data protection laws are violated. However, the laws specify some exceptions in the applicability of data protection laws.

6 Discussion

6.1 Data protection authority

As stated above, we observed that the government plays a critical responsibility in data protection in Africa. The laws stipulated that data protection authorities, which are government agencies, should be established to monitor, administer, regulate, impose sanctions, prosecute violators, and enforce data protection laws. This is similar to what is obtainable under the EU GDPR, where the government-owned supervisory authority plays a crucial function in enforcing data protection laws. Out of the 20 countries selected in this study, 16 countries provide for establishing independent data protection authorities with different nomenclatures. The South African Information Regulator and the Kenyan Office of Data Protection Commissioner are good examples. However, four countries designated a department in existing ministries or agencies to enforce data protection laws, such as the Rwandan National Cyber Security Authority, Eswatini Communications Commission (ESCCOM), Zimbabwe Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority and Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority.

The government, as the regulator of data protection in Africa, has some advantages, including ensuring regulatory compliance, enforcement, and implementation of data protection laws as part of its existing executive functions. This allows for effective coordination with other governmental agencies, such as the police and Information and Communication Commission, as well as competition and consumer protection agencies. Data protection authorities are mostly independent and easily accessible to the public, enhancing public trust and accountability and preventing fraud and cybercrime.

However, it may also lead to excessive government control, such as censorship, limiting freedom of speech and other undemocratic government practices. The Nigerian government’s banning of Twitter is a classic example.133 Also, funding data protection authorities may not be the government’s priority in some African countries due to infrastructure deficits and poor economic development, which may impact their ability to work effectively and hire qualified personnel to investigate data protection violations. Governmental administrative bottlenecks and lengthy procedures may hinder the effective execution of data protection laws. Additionally, the powers of the data protection authorities may be abused by introducing straining or overreaching regulations. The government appoints the boards of data protection authorities, which may give room for political influence in the agencies’ administration. Meddling with the activities of the data protection authorities poses a major challenge to enforcing data protection laws significantly against foreign violators as it reduces confidence in the data protection authorities and may raise fear of victimisation, especially when the government is not a democratically-elected government.

6.2 Administrative sanctions

The data protection authorities can, on their own volition or upon the complaint of a data subject, investigate the violation of data protection laws and issue administrative sanctions. The nature of administrative sanctions includes notice of violation; cessation; the temporary or final withdrawal of authorisation to process data; warning; notice to stop; order to carry out specified steps or measures; refrain from an act; account for profit; compensation to victim; and administrative fines as a financial penalty specified by these African countries. However, the Zimbabwe Data Protection Act does not provide for administrative sanctions.134 Still, it empowers the Zimbabwe Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority to approach the court for any administrative act not in compliance with data protection principles, which takes away the power to levy administrative sanctions from the data protection authority.

The data controllers or processors are mostly notified of their violations and administrative sanctions through an enforcement or penalty notice prescribed by the data protection authority to remedy the breach within a stipulated period, which may also include a penalty. A violator dissatisfied with the administrative sanctions may seek judicial review or appeal to the court within a specified period.135

Giving data controllers or processors notice of violation of data protection practices will make the violator address the complaint and avoid possible future violations by appropriate measures in changing their data protection practices. Also, the fear of sanctions, losing business reputation, public goodwill and customers can make data controllers improve their data proception practices and deter companies and governments from abusing personal data, which will prevent data violations and ensure compliance. However, delayed administrative processes may prolong the issuance of administrative sanctions. Likewise, investigation can be time consuming and requires technical expertise, which may not be readily available. For example, it took about two years for the South African Information Regulator to conclude the investigation and issue enforcement notice 2024 on TransUnion after security breaches were reported in March 2022.136 Delays in the investigation of data protection laws may allow the violators to make profits before or during the investigation of the breach. The profit may not be accounted for if the country does not have an account for profit as an administrative sanction, such as Malawi, Nigeria and Somalia, which require data controllers to account for profit earned due to data protection violations.

6.3 Financial sanctions

As stated earlier, all 20 African countries have a form of financial sanction that is monetary. In these circumstances, violators of data protection laws pay money to the government for non-compliance with data protection laws. Financial sanctions may take the form of administrative fines of a particular amount or a prescribed percentage of the annual return of the data controller in the preceding financial year, as in the case of Kenya, South Africa, Rwanda and Nigeria. For example, the Kenyan Data Protection Act provides administrative fines for up to five million shillings or 1 per cent of annual turnover in the preceding financial year.137 This is similar to what is obtainable under the EU GDPR, where data protection violators can be fined up to €20 000 000 or 4 per cent of the organisation’s global annual revenue in the prior financial year. The significant difference is that the amount was specified in local currency, and the percentage, which we believe is within the peculiarity of each country. However, the administrative penalty in Somalia may be up to US $1 million or its equivalent amount.138

On the other hand, financial sanctions can be specified as fines levied upon conviction, a form of criminal sanctions in countries such as Lesotho, Mauritius, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Therefore, financial sanctions can be administrative sanctions if it is levied by the data protection authority and criminal sanctions if the court imposes them.

Financial sanction serves to generate revenue for the government. For this reason, several African countries will pay more attention to data protection practices in the coming years, especially with Nigeria’s recent imposition of US $220 million on Meta for data protection and consumer practices violations. However, it may leave the victims without compensation for the data breach suffered in the absence of the data subject’s private right of action and data protection law specifying the victim’s compensation as an administrative sanction, as in the case of Malawi, Nigeria and Somalia.

While it is unclear how the violator may pay financial sanctions, it may perhaps be prescribed by the data protection authorities within their general powers of administration of data protection laws. Big corporations can easily afford to pay financial sanctions, like a pin of water in the ocean, especially if the fines were assessed in local African currency and the violators earned revenue in foreign currency. However, smaller corporations may be unable to afford the penalties. They may go bankrupt due to financial sanctions, which is imperative for companies, especially African fintech and start-ups, to take data protection practices seriously. Therefore, examining this aspect of the laws would be a good future study that would shed light on this issue.

6.4 Criminal sanctions

As stated earlier in the result above, all the selected 20 African countries have provisions for criminal sanctions, such as fines, forfeiture and imprisonment terms. Zimbabwe has additional sanctions such as seizure, data deletion and destruction of items.139 Officers and directors of the data controller or processor may be individually criminally liable for violating data protection laws. For example, in Lesotho and Eswatini, if the data controller is a juristic person, the chief executive officer will serve the sentence of imprisonment term imposed on the data controller.140 Corporate data controllers’ employees involved in data protection violations will be personally liable and may be charged for a crime alongside the data controller.141 Additionally, the partner may be jointly and severally liable in Zimbabwe and Zambia, extending this to unincorporated associations. In addition, data controllers can also be vicariously liable for violations caused by their employees, directors and officers.142 Phrases such as ‘juristic person’ or ‘legal person’ and ‘corporate body’ were utilised in the laws, which may include public sector departments and agencies.

Data protection authorities are mandated in most countries to prosecute crimes that contravene data protection laws. However, we observed that in Mauritius, the prosecution of offenders is subject to the permission of the director of public prosecution, which makes us wonder if this will not disturb the independence of the data protection authorities.143

Criminal sanctions will serve a deterrence function as they will make officers of the data controller exercise extreme caution and provide adequate measures while processing personal data, especially because of the personal liability effect. Just like financial sanction, it may not compensate the victim. Even though we did not encounter any criminal prosecution for violation of data protection laws in the selected 20 African countries, criminal sanction may be abused, especially for vendetta or abuse of office. An illustration is the ongoing prosecution of a Binance bitcoin American executive for money laundering after he had travelled to Nigeria to discuss regulatory compliance issues with the Nigerian government.144 This is contrary to what is obtainable under the EU GDPR, which does not provide for the kind of criminal sanctions enumerated in the examined African data protection laws, as privacy violators cannot be charged with criminal offences in the EU. Additionally, the inefficiency of the administration of criminal justice poses challenges that can affect data controllers’ both local and foreign confidence in the application of criminal sanctions as an enforcement mechanism of data protection laws.

6.5 Civil sanctions

Most countries empower data subjects to initiate legal action against data controllers or processors, seeking compensation before a competent court for damages as compensation for a resolution of violation of the data protection laws. The EU GDPR has an equivalence provision on the private right of action. However, there are some exceptions: Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritius, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Zimbabwe data protection laws does not specify the data subjects’ rights to claim damages for privacy violations. Notably, Tanzanian law grants the Personal Data Protection Commission the authority to access compensation and order violators to make payments, which means the data subject will not go through the court system for compensation.

Civil sanction arguably is the best remedy for data subjects who suffered from data protection violations. The victim will be compensated for damage suffered from violating data protection laws. Damage may be extended to ‘financial loss’ and ‘not involving financial loss’ such as ‘distress’.145 It is imperative to note that we did not come across class action as a way of commencing private action against data protection violators in the 20 data protection laws examined. Even though we did not examine the civil procedure laws of each country, there is the likelihood that each data subject may have to instigate a lawsuit for data violation individually, which will increase the number of lawsuits pending before the courts, add to the judges’ workload and may ultimately prolong the duration of administration of justice. However, whether data subjects can access justice using civil sanctions, private right of action, and lack of class action mechanisms can be the subject of another study as it requires empirical data, just like Muhawe and Bashir examined the effect of Article III standing on private right of action in the United States.146

6.6 Registration of data controllers and processors

In the selected African countries in this study, data controllers and processors are obliged to notify and register with the data protection authority before collecting, controlling and processing data or immediately after the collection. Failure to notify or register with the data protection authority is classified as violating data protection laws in many of the selected countries. However, Malawi, Nigeria and Somalia require data controllers or processors of ‘major importance or significance’ to register with the data protection authority, unlike the other countries that make registration mandatory for data controllers and processors.

Registration of data controllers will enable the data protection authorities to have a register of all data controllers and processors in each of the selected countries to monitor compliance. We observed that registration is required before personal data processing in countries such as Eswatini, Mauritius, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. However, in Nigeria and Somalia, data controllers or processors of major importance are obligated to register within six months of reaching the significant importance status.147

However, enforcing mandatory registration of data controllers will be challenging for African data protection authorities against data controllers and processors not resident in Africa but gather, store and process personal data emanating from Africa. For example, challenges such as identifying non-resident data controllers and, in the case of Nigeria, Malawi and Somalia, whether they are data controllers or processors of major significance.

6.7 Compliance audit

Data protection authorities are empowered to conduct periodic data processing audits of data controllers and processors. The purpose of compliance audits under data protection laws is to ensure that data controllers and processors adhere to the laws. Notably, Nigeria, Somalia and Zambia allow data protection authorities to license third-party experts to carry out compliance services.

We observed that many countries, including those with an explicit compliance audit process, included language alluding to routine maintenance and risk assessment. We distinguished general maintenance from compliance auditing by acknowledging that audits signify periodic interventions, not routine impact assessments conducted by data controllers. Another trend noticed and documented in the acts was that traditionally, the audits were stated to be undertaken by either an outside organisation or assigned to a specific role where a phrase similar to ‘is responsible for conducting periodic audits’ is included.

Data controllers and processors are encouraged to employ internal data protection officers or contract organisations rendering data protection services to handle their internal audits before periodic audits by data protection authorities. This will ensure internal compliance and periodic staff training on data protection practices, which will prevent or reduce the effect of violating data protection laws. Additionally, countries such as Egypt, Eswatini, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Somalia, Uganda and Zimbabwe mentioned that data controllers might appoint data protection officers or supervisors.

6.8 Applicability of data protection laws

As stated earlier, we observed that all the 20 selected countries have ensured that their data protection legislations apply to the public and private sectors. This is mainly inferred from the applicability provisions. The Ghanaian Data Protection Act states that the law binds the state. However, there are some instances where data protection legislations are not applicable to every data processor or controller. The instances are personal or household purposes, national public health emergencies, legal claims and defence, criminal investigation and prosecution, public interest, national security and publication, among others.